Lightweight Technical Designs

Scaling down a software architecture approach to smaller teams and -projects

productivity engineering-management software-design howto

Every major undertaking in software engineering at Casper merits a Technical Design Review (TDR), a process that targets stakeholder buy-in, collective thinking, improved cross-functional communication and last but not least providing a reference point for later generations.

While certain intricacies of a TDR are subject to each organization’s individual requirements, we do not divert too much from the suggested process of having the lead engineer(s) write a document, iterating over two or three draft phases, publishing the proposal to the wider team, inviting them to ask their questions in a separate doc and finally sitting down and talk about everything in a synchronous/in-person meeting.

If your organization doesn’t have a formal Technical Design process, yet: check out the excellent article Strengthening Products and Teams with Technical Design Reviews to get started.

What constitutes a “major project” anyway?

There have been over a dozen Technical Designs since the inception of this process at Casper back in early 2017 – including the creation of an internal wholesale order platform, moving our Casper.com frontend to a single page app, conceiving a central repository for product data, and architecting an omni-channel authentication system.

We firmly believe in the advantages of this process and it has served us well. However, there is some leftover ambiguity concerning when exactly we want (or even require) a feature to undergo a TDR.

A Technical Design takes time to write, to review and to discuss. It involves a lot of people. It’s not cheap. The idea is of course that the gains far outweigh the costs but you still want to be mindful when to invest in a TDR. There are some no-brainers: re-platforming parts of your infrastructure, changing your applications’ data interchange format, and swapping out an integral 3rd party API. All of these have two things in common:

- They sound intimidating (well, at first)

- They’re cross-functional

The second part is key. While peer-reviews and constructive feedback from someone with an outside perspective will never hurt the quality of your software product (or anything you do in life for that matter), it doesn’t have to be the formalized procedure as illustrated above when no other parties are concerned.

Software projects in isolation

We should be able to change whatever we want in our software system as long as we stick to our defined and agreed upon external interface.

Not every software project functionally concerns other business units. In fact, it is quite likely the vast majority of your daily work doesn’t. Extrapolating the OOP concept of Information Hiding (and maybe even some sprinkles of Design by Contract) to an organizational level, we should be able to change whatever we want in our software system as long as we stick to our defined and agreed upon external interface.

I’m an avid proponent of Test-Driven Development (TDD) and I feel the temptation to jump right into the action, writing my first set of failing tests, getting them green one by one and iterating until all acceptance criteria are met.

We had a couple of components in our system where Captain Hindsight later said we should have taken more time thinking about the design. There was little to no overlap with other software engineering teams so a TDR didn’t seem appropriate.

Too Long, Didn’t… Write?

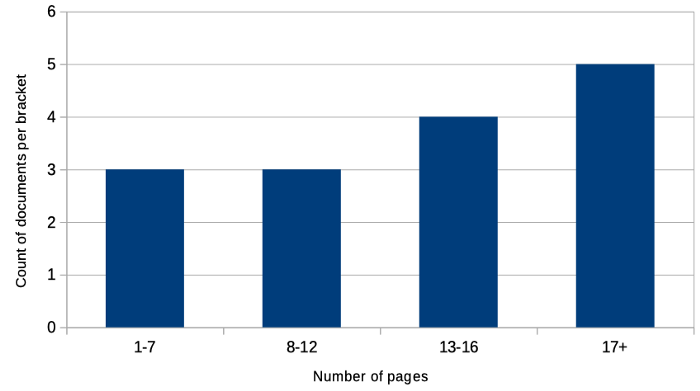

Compiling just the design paper was probably omitted because of uncertainty about what this project would evolve to and also the daunting prospect of losing oneself in details while trying to live up to the scope expectations of a fully featured technical design document: our documents have an average of 15 pages, with close to 30 pages being the upper end.

Distribution: number of documents and their page count

Zooming out for a better perspective, gathering feedback on possible edge-cases a single engineer (or more than one during the resulting code review) may have overlooked, persisting the thought process for future reference, and calling out trade-offs made: those are all desirable things for any software venture — even if its outcome has little to no impact on teams other than yours. What if we just did a smaller version of a TDR?

Sure, there is no written rule about how long a technical design document should be, but having a different name that carries with it the scaled-down scope and slightly altered process with respect to the “original” TDR seemed like a good tool to help distinguish the two siblings.

RFC: Request For Comments

What we initially referred to as “Mini-TDR” later became our RFC format: Request for Comments, borrowing from the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) et al.’s established publication term. Unlike the “real” RFC, it’s not a set-in-stone standard that requires a formal revision process to incorporate changes, but rather a bridge between inviting brevity while still adhering to the general process of a Technical Design Review – albeit significantly smaller in scope. Our key aspects are as follows:

-

RFCs are for bigger-than-average features in your team, they are not for cross-functional ventures. Is this still a qualitative argument? The first condition is, but the latter should be the main differentiator between an RFC and a “real” TDR.

-

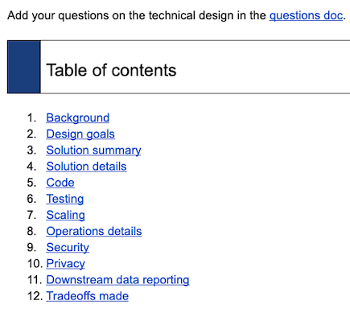

RFC documents are the deliverables for discovery tickets: they outline their findings and proposals. A template can be found here. There is no minimum page count. Be concise.

-

RFC documents are sent to the team that you’re immediately working with. Team members are invited to use the built-in comment function of your collaboration tool of choice, quite akin to the feedback cycle you know during Pull Request reviews

-

The RFC’s author sends an invite for a synchronous meeting. This is not exclusively just for members of your team, you may invite selected members of other teams.

Conclusion

At the time of writing we had two RFCs. Their documents provided a sketch of possible implementations as well as detailed background information that formed the foundation of a constructive team conversation.

It is of course difficult (read: impossible) to peek into alternate timelines that didn’t have us doing the RFC exercise for the bigger-than-average features that these two RFCs targeted, but the discussion and focus on the design expectations and implications certainly made us confident about the chosen path.

The lean RFC process didn’t get in the way and rather helped guiding both the design considerations as well as the ensuing conversation about it. It fit naturally into our Sprint.

Does it invalidate the need for “real” Technical Design Reviews? No. As its smaller sibling it’s another tool in the box, targeting different requirements and audiences while sharing tried and proven concepts with its relative.

comments powered by Disqus